The Buyback Mirage – How EPS Gets a Cosmetic Lift – Real EPS Growth vs. Finance Magic

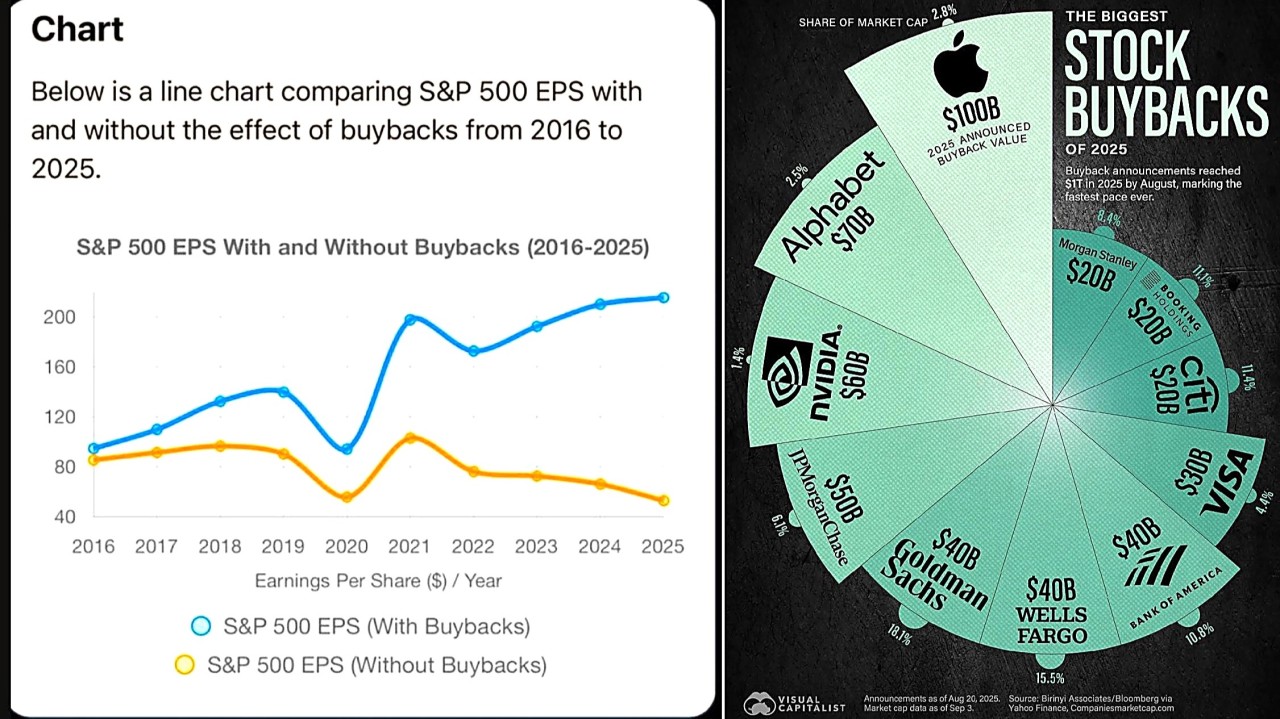

Corporate share buybacks are back in the headlines. In 2025, U.S. companies announced buybacks exceeding about $1 trillion by August, led by technology and financial majors. India has seen activity too: listed firms repurchased roughly ₹48,000–49,000 crore (~$5.8 billion) in 2023 and about ₹13,500 crore (~$1.6 billion) in 2024, with large, cash-rich companies like Infosys undertaking repeated programmes. These figures sound impressive, and buybacks often lift stock prices in the short run. But the finance behind them is subtle. This note explains, in simple terms, why buybacks can create an artificial sense of earnings growth, why valuations sometimes rise on optics rather than economics, and why reinvestment, especially in growing markets like India, usually drives superior long-term results.

What a buyback actually does

When a company buys back its own shares, it reduces the number of shares outstanding. Mathematically, earnings per share (EPS) increase even if total profit does not change. If a firm earns ₹10,000 crore and has 1,000 crore shares, EPS is ₹10. After a 5% buyback (share count falls to 950 crore), EPS becomes ~₹10.53 without any improvement in sales, margins or cash flows. Price/earnings (P/E) can appear cheaper, and the stock may rise. But the operating engine is unchanged.

From a corporate-finance lens, this is a payout decision just like a dividend, but executed by purchasing shares rather than sending cash to bank accounts. Under the famous Modigliani–Miller logic (perfect markets, no taxes, no frictions), payout form does not create value; only positive-NPV investments do. In the real world, taxes, signalling and market microstructure matter, so buybacks can have effects—but these are essentially distribution mechanics, not value creation by themselves.

EPS growth vs economic growth

Analysts should separate accounting ratios from economic value:

A cleaner lens is the value growth equation:

Long-run growth (g) ≈ Reinvestment Rate × Incremental ROIC (return on invested capital).

If a company stops reinvesting and returns most cash via buybacks, its reinvestment rate falls. Unless incremental ROIC was low or opportunities were absent, that decision lowers g. If the market valuation still assumes high growth (say 10–12%), the P/E today embeds reinvestment that may never materialise. In time, the share may face a de-rating when reality catches up.

Why buybacks can appear to “work”

Three forces make buybacks look powerful:

None of these forces guarantees sustainable value creation. They improve per-share optics and sometimes short-term returns, but they do not, by themselves, expand the company’s productive capacity.

India’s context: a reinvestment market

India remains a growth market, with opportunities arising from formalisation, infrastructure, manufacturing, digitisation, and rising consumption, where incremental ROIC can exceed 15-20%. In such an environment, every rupee retained and reinvested in the core business can compound intrinsic value faster than a rupee spent on buybacks, especially when share valuations are already rich.

The local data are instructive. Buyback totals of about ₹48,000–49,000 crore (~$5.8bn) in 2023 and ₹13,500 crore (~$1.6bn) in 2024 are meaningful, yet small relative to India’s capex cycle and funding needs. Several large firms have conducted repeated buybacks; cumulatively, some programmes (e.g., in IT services) run into tens of thousands of crores (~$4-5bn). These are legitimate ways to return cash, but for high-ROE/high-ROIC businesses with a long runway, reinvestment usually dominates over time.

When buybacks make sense and when they don’t

In corporate-finance terms, capital allocation follows a hierarchy:

For beginners: think in NPV. If the IRR on reinvestment is comfortably above the cost of capital, keep building. If not, return cash, and if buying back, ensure the repurchase price < intrinsic value. EPS accretion is not the test; per-share intrinsic value accretion is.

The valuation illusion

High-quality businesses often command premium multiples because investors expect sustained reinvestment at high incremental returns. If management instead runs large buybacks year after year, the company’s reinvestment rate quietly falls. Growth slows from, say, 12% to 4-5%, yet the stock might still trade at a multiple that assumes 12%. For a while, the EPS still rises (because share count falls), and valuation holds up. Eventually, the market notices the slower engine and the multiple compressions. The earlier outperformance then looks artificial, driven by accounting arithmetic and multiple support, not by true expansion of cash flows.

How other markets compare

The common theme is that buybacks are most celebrated in situations where mature businesses generate cash faster than they can find high-return projects. In younger, faster-growing economies, reinvestment typically delivers better compounding.

High-ROE is not a licence to repurchase

A frequent misconception is: “Our ROE is 20%+, so buybacks must be great.” Not necessarily.

The correct question is not, “Will the buyback raise EPS?” It is, “Does the buyback raise intrinsic value per share more than the next best use of cash?”

A simple checklist for investors and students

India’s edge: compounding through reinvestment

For India, the message is clear. We are in a multi-year cycle of capex, formalisation and productivity gains. Many companies can still reinvest retained earnings at attractive rates. That makes reinvestment the first call on cash, not buybacks. Of course, if a stock is trading well below intrinsic value, a measured buyback can be value-accretive after growth projects are funded and balance sheet strength is preserved.

The message behind the scenes

Buybacks are a tool, not a strategy. They are excellent when they transfer cash to shareholders at the right price and after funding high-return growth. But they do not create new cash flows by themselves. Markets that rely heavily on buybacks may show strong per-share optics and higher valuations. Yet, part of that return is manufactured by arithmetic and scarcity, not by expansion of the economic engine. Markets that prioritise reinvestment at high incremental returns—like India today—tend to deliver truer, more durable compounding.

Invest where the next rupee earns more than the last. EPS can be engineered; intrinsic value must be built.

Author:

Mr. Biharilal Deora, Director @ Abakkus Asset Manager

Volatility risk is well known, but that is usually less dangerous Retirees fear market volatility, and volatility is a risk…

For NISM, 2025 was defined by a renewed commitment to capacity building and investor education. Anchored by our mandate from…

The threats of money laundering (ML) and terrorist financing (TF) have grown exponentially due to the increasingly interconnected nature of…

© 2026 National Institute of Securities Markets (NISM). All rights reserved.