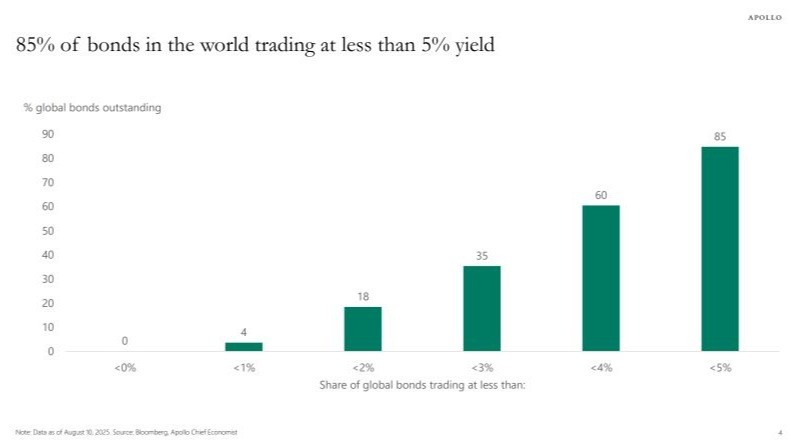

The global bond markets are a significant indicator of the current financial landscape. With nearly 85% of outstanding bonds now trading at yields below 5%, it’s clear that we’re witnessing profound structural shifts in global credit, corporate balance sheets, and investment cycles. This low-yield environment carries significant consequences for companies, policymakers, and investors, and it’s crucial to understand its implications.

When interest rates remain compressed, firms with outstanding borrowings find it much easier to refinance. Instead of paying 6-7% on old loans, they can now roll them over at 3–4%. The advantages are obvious: a lower interest bill that directly boosts profitability, and longer debt maturities that strengthen financial resilience. In other words, low yields quietly act as a tailwind, reducing financing pressure without the need for revenue growth.

Another hallmark of this cycle is the exceptionally low level of defaults. S&P Global data shows that global corporate defaults in 2024 were around 2%, well below the long-term average of 4-5%. A significant factor contributing to this is the deleveraging that occurred following the COVID years. Global corporate leverage, measured by Net Debt to EBITDA, has improved from about 3.2x in 2020 to roughly 2.6x in 2025. US companies alone reduced net debt by more than $500 billion between 2021 and 2023, while European corporates also cut leverage to multi-year lows. With stronger balance sheets and fewer defaults, creditors are more willing to lend, and companies are in a better position to pursue new projects with less risk.

Normally, such conditions would trigger a fresh borrowing and investment cycle. With capital available at 3-4%, project hurdle rates drop, and more projects become viable. We saw something similar in the early 2000s, when low post-2001 rates led to a surge in global capex and strong emerging-market growth. Yet today, the pattern is slightly different. Despite cheap debt, many multinational companies are funding growth using equity and internal accruals instead of piling on leverage. The scars of past excesses are still visible, and corporates appear far more disciplined this time around.

For India, this global backdrop is especially encouraging. Indian corporates already rank among the least leveraged in the world. Net Debt to EBITDA for NSE India Nifty 500 companies has fallen sharply to ~1.2x in FY25, compared with over 2.5x just ten years ago. Leading groups such as Reliance, Tata, and Aditya Birla are consciously financing expansion through equity, retained earnings, and strategic partnerships rather than relying solely on bank borrowings. In FY25, corporate capex crossed ₹11 trillion (about $126 billion), and a large share of this was equity-financed. This approach ensures that Indian corporates can continue investing aggressively while keeping their balance sheets healthy.

When we look at the past 15 years, the contrast becomes even clearer. Globally, leverage has only fallen modestly, from ~3.2x in 2020 to ~2.6x today. Indian companies, on the other hand, have almost halved their leverage over the last decade. This unique position of India, entering a capex upcycle from a position of balance-sheet strength, is a reason for optimism about India’s financial future.

The last time yields were this low on a global scale was after 2008, during the era of quantitative easing. That phase was marked by heavy debt issuance but also unsustainable leverage. The present environment is different. Corporates are refinancing with caution, not over-borrowing. Indian firms are expanding with limited leverage, and equity-funded capex is reducing systemic risks while still driving growth.

For investors, the implications are straightforward. Fixed-income returns are compressed, encouraging greater flows into equities and alternatives. India, in particular, stands out. Strong corporate balance sheets and disciplined financing underpin growth here. The combination of deleveraging and rising capex is rare and history shows that such a backdrop often precedes multi-year equity market cycles.

The global low-yield environment, therefore, presents a rare alignment: cheaper refinancing, low defaults, and healthier balance sheets. For India, the alignment is even stronger. With corporates already deleveraged and capex mainly funded through equity, the country could be on the verge of its most sustainable growth phase in decades. For investors, the lesson is clear: when debt is cheap and balance sheets are strong, growth cycles tend to follow and India is exceptionally well placed to benefit.

Author:

Biharilal Deora, Director @ Abakkus Asset Manager

The Budget 2026 brought a huge setback for the Sovereign Gold Bond (SGB) investors. Before Budget 2026, all redemptions of…

Volatility risk is well known, but that is usually less dangerous Retirees fear market volatility, and volatility is a risk…

For NISM, 2025 was defined by a renewed commitment to capacity building and investor education. Anchored by our mandate from…

© 2026 National Institute of Securities Markets (NISM). All rights reserved.